Standalone Functions and Object Functions

Way back in Chapter 2, we learned how to create functions. Here’s a very simple function that puts single quotes at the beginning and the end of a String:

fun singleQuoted(original: String) = "'$original'"As you recall, this function can be called easily, like this:

val title = "The Robots from Planet X3" val quotedTitle = singleQuoted(title) println(quotedTitle) // 'The Robots from Planet X3'And then in Chapter 4, we learned that objects can contain functions, too. For example,

Stringobjects have a function nameduppercase()that returns the same string, but with all uppercased letters. You can call it like this:val title = "The Robots from Planet X3" val loudTitle = title.uppercase() println(loudTitle) // THE ROBOTS FROM PLANET X3When you call a function that’s on an object like this, you prefix the function call with the name of the object and a dot. For this reason, this way of writing a function call is called dot notation.

So, we have two different categories of functions here:

- Functions that stand alone, apart from an object.

- Functions that are called on an object.

It’s easy to call a standalone function. It’s also easy to call a function on an object.

However, things become more difficult when you combine calls to these two different types of functions in one place. Take a look at this code, which calls one standalone function (

singleQuoted()), and calls two functions with dot notation (removePrefix()anduppercase()).singleQuoted(title.removePrefix("The ")).uppercase()Can you figure out what order will these functions will be called in?

- First,

removePrefix()is called.- Then, the result from that call will be used as an argument to the

singleQuoted()function.- Finally,

uppercase()will be called on the string object that is returned fromsingleQuoted().Visually, our minds have to process this expression by bouncing around - starting in the middle, then moving to the left, then moving to the right.

Imagine trying to read a book like this!

It would be easier to read and understand the code if all three of these function calls worked the same way, so that we could read them in a single direction. For example, if you could use dot notation to call the

singleQuoted()function - just like you do withremovePrefix()anduppercase()- then it would be very easy to follow. Here’s what that would look like:val newTitle = title.removePrefix("The ").singleQuoted().uppercase()Since

singleQuoted()isn’t a part of theStringclass, this code doesn’t actually work yet. But you can certainly see how much easier it is to read and understand it, because the functions are called in the same order that you read them. You can simply follow the code from left to right.These calls could also be arranged vertically, one per line, like this:

val newTitle = title .removePrefix("The ") .singleQuoted() .uppercase()Again, it’s natural to read - from top to bottom.1

Besides making the function calls consistent and easy to read, there are times when dot notation just fits well with a Kotlin developer’s expectations. By convention, if a function primarily does something to an object or with an object, then we often expect that function to exist on the object.

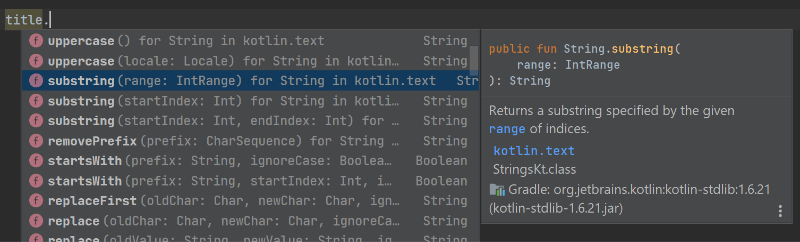

Also, if you’re using an IDE like IntelliJ or Android Studio, functions that are “on an object” are easier to discover. If you’ve got a

Stringobject, and you wonder what functions can be called on it, just type the dot, and you’ll see a list of the available functions! This is a great way to explore classes that you’re not as familiar with.

So, in this chapter, our goal is to change

singleQuoted()so that it can be called with a dot, like this:val newTitle = title.singleQuoted()Let’s start by looking more closely at the similarities and differences between standalone functions, and those that are called on an object.

They’re Not So Different After All

These two categories of functions - standalone functions and functions that are called on an object - have more in common than you might think. Yes, the way that you have to write the code - that is, the syntax - to call the function is a little different in each case:

But in concept, they’re actually very similar:

- They both start off with a string.

- They both return a new string that is based on the original string.

From that standpoint, it’s almost as if each of these functions takes a

Stringargument. The difference is only in where you put that argument when you call the function.When calling a function using a dot, the object to the left of the dot is called the receiver of the function call. Receivers are an important concept for this chapter, but they’re also important for understanding upcoming concepts like scope functions and more advanced lambdas, so let’s dig in!

Introduction to Receivers

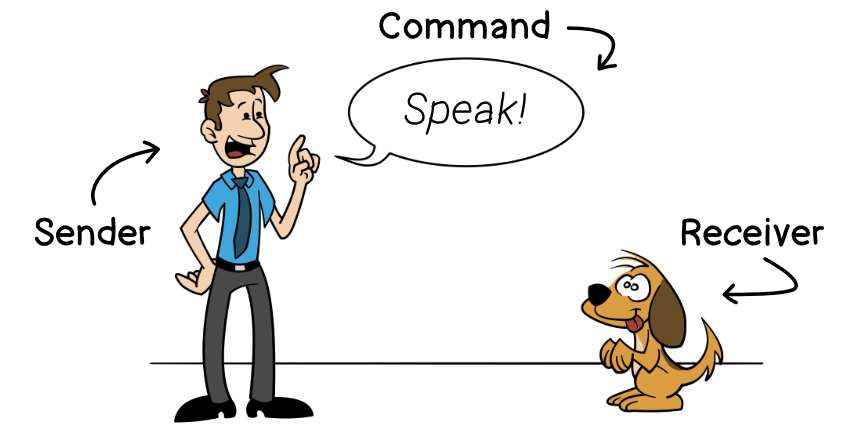

A well-trained dog knows how to bark on command. When you tell your dog Fido to “speak”, you’re sending him a command, and he is the receiver of that command.

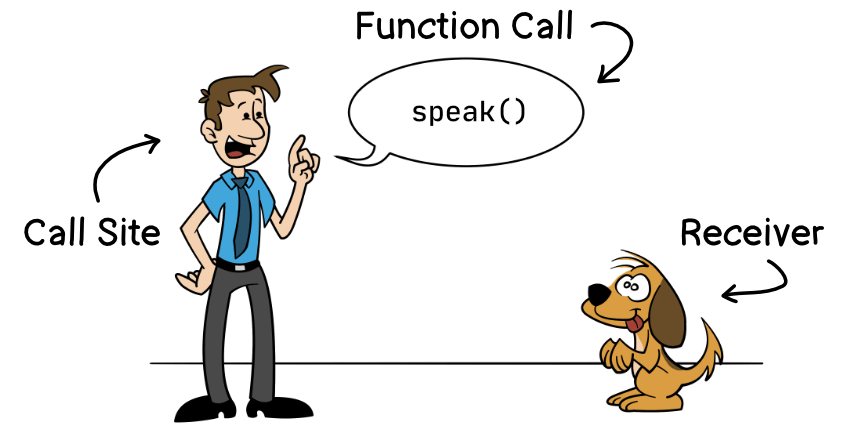

Similarly, when you call a function on an object, that object is the receiver of that function call.

Let’s flesh this out further with some code. Here’s a simple

Dogclass, followed by some code to tell the dog to speak.class Dog { fun speak() { println("BARK!") } } val fido = Dog() fido.speak()Since

fidois the dog you’re telling tospeak(),fidois the receiver.Easy, right?

Now, sometimes your dog doesn’t need to be told to speak. Sometimes he will choose to bark on his own. (In fact, sometimes you can’t get him to stop barking… ask me how I know!)

Let’s update the

Dogclass so that Fido will bark whenever he starts playing.class Dog { fun speak() { println("BARK!") } fun play() { this.speak() } }Here, the

play()function calls thespeak()function. As you might recall from Chapter 4, the keywordthisrefers to the same object thatplay()is called upon. In other words, if you callfido.play(), thenspeak()will be called on thefidoobject. In Listing 10.9, the receiver of thespeak()function call isthis.You might also remember that you can omit

this., so the following code works the same as the code in the previous listing.class Dog { fun speak() { println("BARK!") } fun play() { speak() } }Now, there’s no object name or dot before

speak(); just the function name. Does this mean that there’s no receiver here?In fact, there is a receiver here! Remember - any time that a function is called on an object, that object is the receiver. Because

speak()is being called on aDogobject, that object is the receiver. Inside theplay()function, you can includethis.beforespeak(), or you can omit it. The result is the same either way, and the receiver is the same either way.So,

speak()has a receiver here! It’s just not explicitly stated in the code. It’s implied. That’s why this is called an implicit receiver. Contrast this with the explicit receiver in Listing 10.8 above. The following shows two call sites forspeak()- one that’s using an implicit receiver, and one that’s using an explicit receiver.Wow, that’s a lot of information about receivers, but we can summarize it like this:

- A receiver is an object whose function you are calling.

- It can either be explicit, as seen when calling a function with a dot, or…

- It can be implicit, such as when one function calls another function inside the same class.

Now that we know about receivers, we can use this knowledge to get back to our original goal - updating the

singleQuoted()function, so that we can call it with a dot.Introduction to Extension Functions

As it’s currently written, the

singleQuoted()function has a single parameter, calledoriginal, which is the string that will be wrapped with quotes. All we need to do now is to update the function so that it has a receiver instead of a normal function parameter.When you want to be able to call a function with a dot, one way to do this is to add the function to the class. However, you can’t always do this. The

Stringclass is part of the Kotlin standard library, so you can’t just open up its code and write a new function in it!Thankfully, Kotlin provides a way to extend a class with your own functions, which can be called with a dot. These are called extension functions.

Let’s look at the

singleQuoted()function that we wrote way back at the beginning of this chapter.fun singleQuoted(original: String) = "'$original'"Let’s change the

originalparameter to be the receiver, so thatsingleQuoted()will be an extension function. It’s easy to do:

- First, prefix the function name with the type of the receiver that you want, and add a dot. In this case, we want a receiver that’s a

String.- Second, refer to the receiver using

thisinside the function body.Here’s how

singleQuoted()looks after making these changes:fun String.singleQuoted() = "'$this'"In this code:

Stringis the receiver type. By specifying this asString, you’ll be able to callsingleQuoted()on any object that is aString.thisis the receiver parameter. It refers to whatever objectsingleQuoted()is called upon, so if you calltitle.singleQuoted(), thenthiswill refer to thetitleobject.You can easily convert a regular function to an extension function:

- Put the type of the parameter before the function name, and add a dot.

- Anywhere you used that parameter, rename it to

this.- Finally, remove the original parameter from between the parentheses.

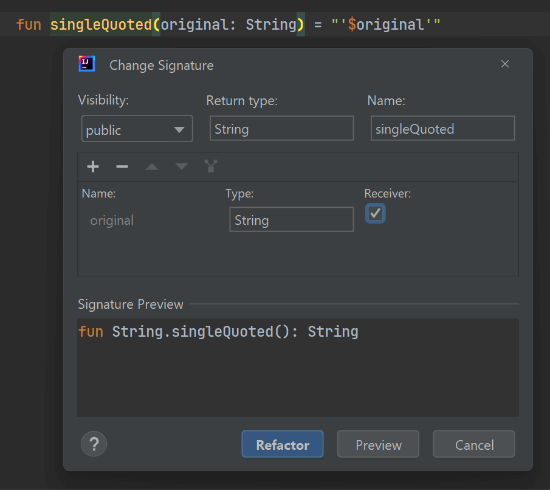

If you’re using IntelliJ or Android Studio, you can also convert a function to an extension function by using the refactoring tools. To do this, right-click the function name, then choose “Refactor” and “Change Signature”. From there, check mark the parameter that you want to convert to a receiver.

With these changes, whenever you call this function, you must call it with a receiver, like this:

val quotedTitle = title.singleQuoted()And now, it’s easy to insert this function call into the middle of a call chain:

val title = "The Robots from Planet X3" val newTitle = title .removePrefix("The ") .singleQuoted() .uppercase() // 'ROBOTS FROM PLANET X3'Extension functions are quite common in Kotlin code. Kotlin’s standard library includes many extension functions, too. In fact, you might be surprised to learn that both

removePrefix()anduppercase()are not actually members of theStringclass - they’re extension functions, too!Extensions are a great way to give an existing type some new functionality, especially for classes where you can’t edit the class itself. Just keep in mind that extensions cannot access

privatemembers of a class. So, even though an extension function is called the same way as a member function, it doesn’t have access to all of the same things that a member function does!Nullable Receiver Types

What happens when you want to call an extension function on a nullable object?

You’ll get an error message.

val title: String? = null val newTitle = title.singleQuoted()ErrorAs you might remember from Chapter 6, you can work around this by using the safe-call operator

?.so thatsingleQuoted()is only called whentitleis not null.val title: String? = null val newTitle = title?.singleQuoted()Kotlin also gives you another option, though - you can create an extension function that has a nullable receiver type. For example, instead of making the receiver type a non-nullable

String, you can make it a nullableString?, like this:fun String?.singleQuoted() = if (this == null) "(no value)" else "'$this'"Inside this function,

thisis nullable. If this version ofsingleQuoted()is called on a null, then it returns a string that says(no value). Otherwise, it works like the previous version ofsingleQuoted(), as in Listing 10.12.When an extension function has a nullable receiver type, you don’t have to call it with a safe-call operator. You can call it with a regular dot operator instead.

val title: String? = null val newTitle = title.singleQuoted() println(newTitle) // (no value)On the other hand, you could still choose to call it with the safe-call operator if you want, but in that case, the function will only be called if the receiver is not null. For example, the only difference between the following listing and the previous listing is that we changed from a regular dot operator to the safe-call operator. The result is that

newTitleisnullrather than(no value).val title: String? = null val newTitle = title?.singleQuoted() println(newTitle) // nullSo, choose carefully between a dot operator and a safe-call operator, based on your expectations.

Extension Properties

In addition to extension functions, you can also create extension properties. However, you can’t use an extension property to actually store additional values inside a class. For example, it’s not possible to add an ID number to a

String. Still, they can be helpful for making small calculations.Let’s create an extension property that tells us if a

Stringis longer than 20 characters.val String.isLong: Boolean get() = this.length > 20Just as with an extension function, an extension property specifies the receiver type, and the receiver parameter is available as

this.As mentioned before, when you’re calling a function or property on an implicit receiver, you don’t need to include

this., so you could also write this property without it:val String.isLong: Boolean get() = length > 20You can use this property the same way as you’d use any property:

val string = "This string is long enough" val isItLong = string.isLongSummary

In this chapter, you learned:

- The difference between standalone functions and object functions.

- All about explicit and implicit receivers.

- How to create an extension function.

- How to create an extension function that has a nullable receiver type.

- How to create an extension property.

In the next chapter, we’ll learn about Scopes and Scope Functions. Kotlin developers use scope functions frequently, and in some cases, they can even be a helpful replacement for extension functions. See you then!

Thanks to David Blanc and Matt McKenna for reviewing this chapter.

When the functions are called in the same order as you’d naturally read them (that is, left to right, top to bottom), developers often refer to this as a fluent interface. However, Martin Fowler and Eric Evans, who came up with that term, clarify that using chained function calls is only part of what makes an interface fluent. Read more thoughts about fluent interfaces from Martin Fowler. ↩︎